Virginia’s barrier islands make up the longest stretch of undeveloped shoreline on the eastern seaboard and it’s a kayaker’s paradise. The seaside of Virginia’s eastern shore region is home to over a dozen barrier islands, all of which are undeveloped, uninhabited, and simply put, wild. The labyrinth of marsh creeks leading from the mainland to the islands is any paddler’s dream, and once you step foot on one of the islands, you’ll undoubtedly be overcome with a feeling of peace and solitude that most people will never experience in an entire lifetime.

Most of the barrier islands are open to low-impact, day-use recreation such as kayaking, but it’s important to understand the ecological importance of the islands and associated visitation restrictions before venturing out to see them. A great resource for planning your trip to any of the barrier islands is Explore Our Seaside, a comprehensive website that is super easy to navigate and is packed with helpful tips for making the most of your visit and minimizing your impact on the fragile ecosystem.

Most of the barrier islands are open to low-impact, day-use recreation such as kayaking, but it’s important to understand the ecological importance of the islands and associated visitation restrictions before venturing out to see them. A great resource for planning your trip to any of the barrier islands is Explore Our Seaside, a comprehensive website that is super easy to navigate and is packed with helpful tips for making the most of your visit and minimizing your impact on the fragile ecosystem.

It’s also extremely important to understand that kayaking out to the barrier islands is NOT for beginners. Strong and sometimes unpredictable tidal currents can threaten even an experienced paddler. Barrier islands are also extremely dynamic places, constantly being molded and reshaped by coastal storms, currents, and tides. What was a navigable channel last year, might not be passable next year. If you’re not experienced enough to paddle out to the islands alone, be sure to hire a certified Eco-Tour Guide to help you get there safely.

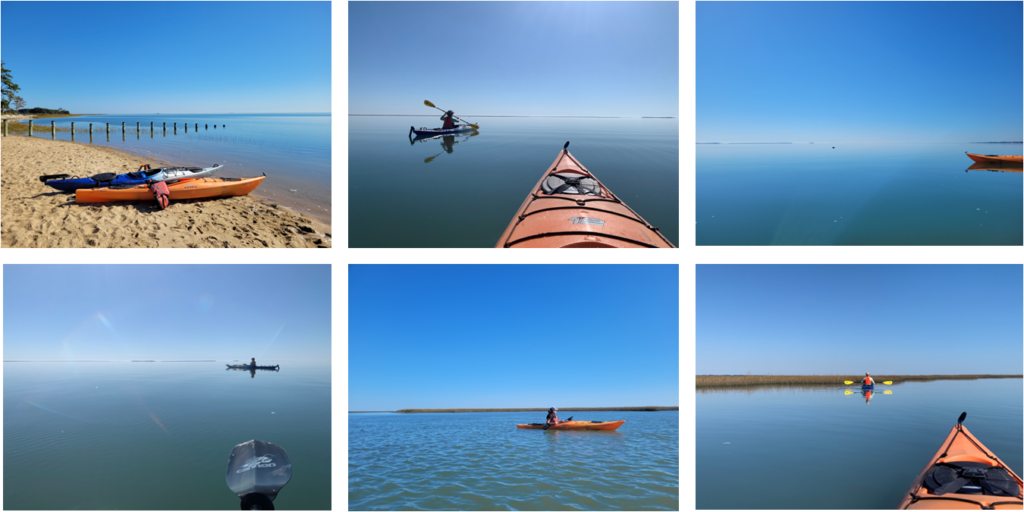

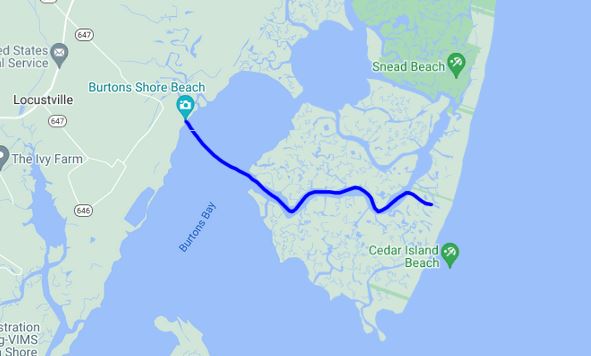

Two of our Virginia Water Trails team recently paddled out to Cedar Island, located about 25 miles south of Chincoteague, and just a few miles north of Wachapreague. We launched from Burton’s Shore, a small public beach outside the town of Accomac. Winds were predicted to be around 5 knots, out of the north and switching to east later in the day, which was perfect for our excursion. We started paddling right around high tide, so the tide was going out for our entire adventure.

Two of our Virginia Water Trails team recently paddled out to Cedar Island, located about 25 miles south of Chincoteague, and just a few miles north of Wachapreague. We launched from Burton’s Shore, a small public beach outside the town of Accomac. Winds were predicted to be around 5 knots, out of the north and switching to east later in the day, which was perfect for our excursion. We started paddling right around high tide, so the tide was going out for our entire adventure.

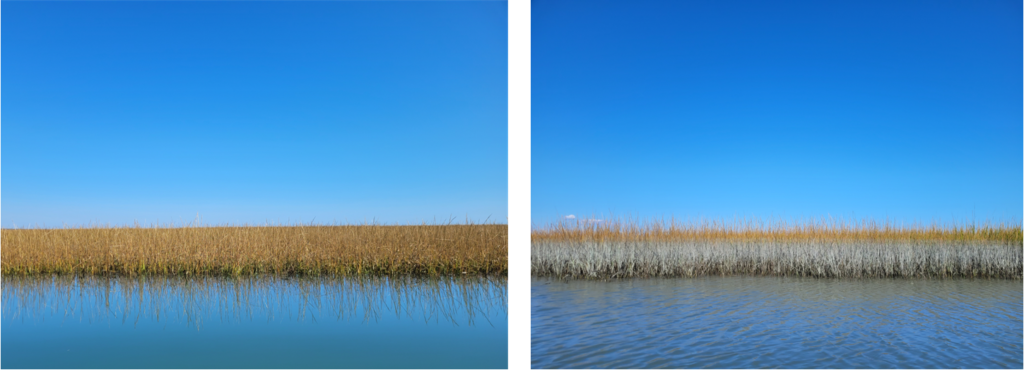

It was about a mile across Burtons Bay and the water was like glass. At times it was hard to tell where the horizon was! But as we reached the marshes on the backside of Cedar Island, we quickly located the creek that would lead us to the beach, and we also started to spot sand dunes and hear waves crashing in the distance.

It was another two miles of paddling through the marsh creeks to reach the island. Because we were paddling about halfway between Wachapreague Inlet and Metompkin Inlet, we weren’t sure which way the outgoing tide would be flowing, but as we headed into the creek, it became quite apparent that the outgoing tide in this section of the creek (known as the Great Channel) was headed south to Wachapreague inlet; we were fighting the current the whole way up the creek. We were only two days off from the full moon too, so the tidal coefficient was pretty high as well.

We took a right turn out of the Great Channel into a narrower creek that allowed us to kayak right up to the barrier island. That creek was shallow, so we made sure to not linger too long on the beach – the last thing we wanted was to trek through the marsh mud because the tide had gone out too far.

As we walked from the marsh to the ocean side of the island, we startled two bald eagles and they promptly took off from the beach and headed north. They probably weren’t expecting us and it’s quite possible that they hadn’t seen humans on the island for days. Other wildlife sightings that day were pretty scarce, but one creature that we saw in abundance was the ghost crab. Ghost crabs are typically nocturnal creatures, but for some reason they were out in the middle of the day in masses! As we sat on the sand to eat our lunch, we saw countless crabs running in all directions, sometimes directly toward us as if they were going to swipe some snacks!

As we walked from the marsh to the ocean side of the island, we startled two bald eagles and they promptly took off from the beach and headed north. They probably weren’t expecting us and it’s quite possible that they hadn’t seen humans on the island for days. Other wildlife sightings that day were pretty scarce, but one creature that we saw in abundance was the ghost crab. Ghost crabs are typically nocturnal creatures, but for some reason they were out in the middle of the day in masses! As we sat on the sand to eat our lunch, we saw countless crabs running in all directions, sometimes directly toward us as if they were going to swipe some snacks!

Since it was mid-October, we didn’t see the typical beachnesters and marsh birds we might see in the peak summer season, but that was actually a good thing. Many of Virginia’s barrier islands are off limits to visitation above the high tide line in the summer. Restrictions are typically lifted in September. In fact, if we had paddled the same route and walked out to the ocean in the summer, we would have been violating those restrictions and potentially trampling vital nesting habitat for birds like piping plovers, American oystercatchers, and least terns. Due to heavy development on other barrier islands in the mid-Atlantic, birds that nest exclusively on beaches like these have experienced immense habitat loss, making these barrier islands all the more ecologically important.

Speaking of development, as we sat on the beach in awe of our beautiful surroundings, we couldn’t help but imagine what Cedar Island could have been. As early as the 1950s, Cedar Island was subdivided into thousands of lots with the intention of creating an “Ocean City, VA.” Luckily, there were no solid plans for the construction of a bridge from the mainland to Cedar Island, so a “city” never came to fruition. But that didn’t stop a good handful of lots from being sold for development in the 1980s and as late as the 1990s. Well over a dozen houses were constructed, but with a few coastal storms and natural barrier island migration, a handful of the homes were quickly destroyed, some of which were still under construction. By 2013, only four houses remained; three homes on the south end of the island, and the 1935 Coast Guard station on the north end.

Today, the old Coast Guard Station is the only structure that still remains on Cedar Island. It was removed from the U.S Coast Guard’s list of active stations in 1964 and is now privately owned. It is interesting to note that the one building built in the 1930s has outlived all the other structures built decades later. It’s almost as if the early Coast Guard knew something about Cedar Island that all of those beachfront-hungry homeowners were oblivious to.

Once we finished up our lunch, we decided to walk a little ways down the beach. Knobbed and channeled whelks were everywhere, making for a beachcomber’s dream come true. The ghost crabs were eyeing us up everywhere we turned. And the silence of being miles away from civilization was breathtaking. As we were returning to our kayaks, several semipalmated plovers flew by us and off over the marsh, reminding us that this island belonged to them, and we were just mere visitors admiring their home for just a tiny slice of the day.

Once we finished up our lunch, we decided to walk a little ways down the beach. Knobbed and channeled whelks were everywhere, making for a beachcomber’s dream come true. The ghost crabs were eyeing us up everywhere we turned. And the silence of being miles away from civilization was breathtaking. As we were returning to our kayaks, several semipalmated plovers flew by us and off over the marsh, reminding us that this island belonged to them, and we were just mere visitors admiring their home for just a tiny slice of the day.

We effortlessly cruised quickly back down the creek and into Burton’s Bay on the outgoing tide. The wind switched to be out of the east, as forecasted, which aided us in our return to the mainland.

We found ourselves wanting to return for longer and more frequent trips to the barrier islands because the beauty and remoteness is unmatched anywhere else. But at the same time, we recognized that the more we visit, the less wild Cedar Island and all the other islands become, so we opted not to visit again this season and just let the island… be.

The magic of kayaking to Virginia’s barrier islands deserves to be shared. But at the same time, we encourage all visitors to do as we did, and explore responsibly, safely, respectfully, and in moderation. Places like Cedar Island are fragile and finite, and we must all do our part to protect them and ensure they exist for many more generations to enjoy.

Helpful Resources:

Map of Our Route to Cedar Island

Virginia Institute of Marine Science

Virginia Water Trails Eastern Shore Map

About the Author: Laura Scharle lives on the Eastern shore of Maryland and is a frequent paddler in coastal Virginia. She is a Virginia certified ecotour guide and is an independent marketing contractor with a focus in ecotourism and heritage tourism. Laura can be reached through our Eastern Shore ecotour guide listings.