Even the most passionate environmentalist can’t compete with the oyster.

One oyster can filter as many as 50 gallons of water a day, removing pollutants such as nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon. The reefs they establish attract multiple other habitats for species of shellfish and fish, contributing to a healthier ecosystem.

That impact fueled Mike Congrove into becoming an entrepreneur after planning a career in marine science. An internship as a mate on an oyster restoration boat turned him on to the idea of aquaculture. He knew if he went into the business of oyster restoration, it had to be self-sustaining. Building a shellfish hatchery to benefit the Chesapeake Bay became a goal.

“I’m in the business of growing baby oysters,” Congrove said.

The Virginia Institute of Science alum owns and operates Gwynn’s Island-based Oyster Seed Holdings, which cultivates and sells Chesapeake Bay oyster seed to shellfish farmers. The company that started in 2009 and Congrove purchased in 2014 is both independent and innovative, adopting a tech-forward approach to developing and supporting products to support oyster production.

Generations of watermen have made a living in Mathews County largely through wild seafood capture. “This is the next generation of that,” Congrove said. “There are still plenty of ways to make a living on the water. Oyster aquaculture is one of those.”

Oyster Seed Holdings starts its operation by relying on broodstock from VIMS and essentially tricks the oysters into thinking it’s summer. Oysters spawn from June through August locally but by adjusting the water temperature in holding tanks to between 75 and 78 degrees, the oysters think it’s June or July. That allows the company to spawn oysters January through August.

“You can compare the process to a chicken hatchery,” Congrove said. “Chicken farmers don’t hatch their own chicks. Oyster farmers don’t hatch their own oysters. They’re made here in the hatchery.”

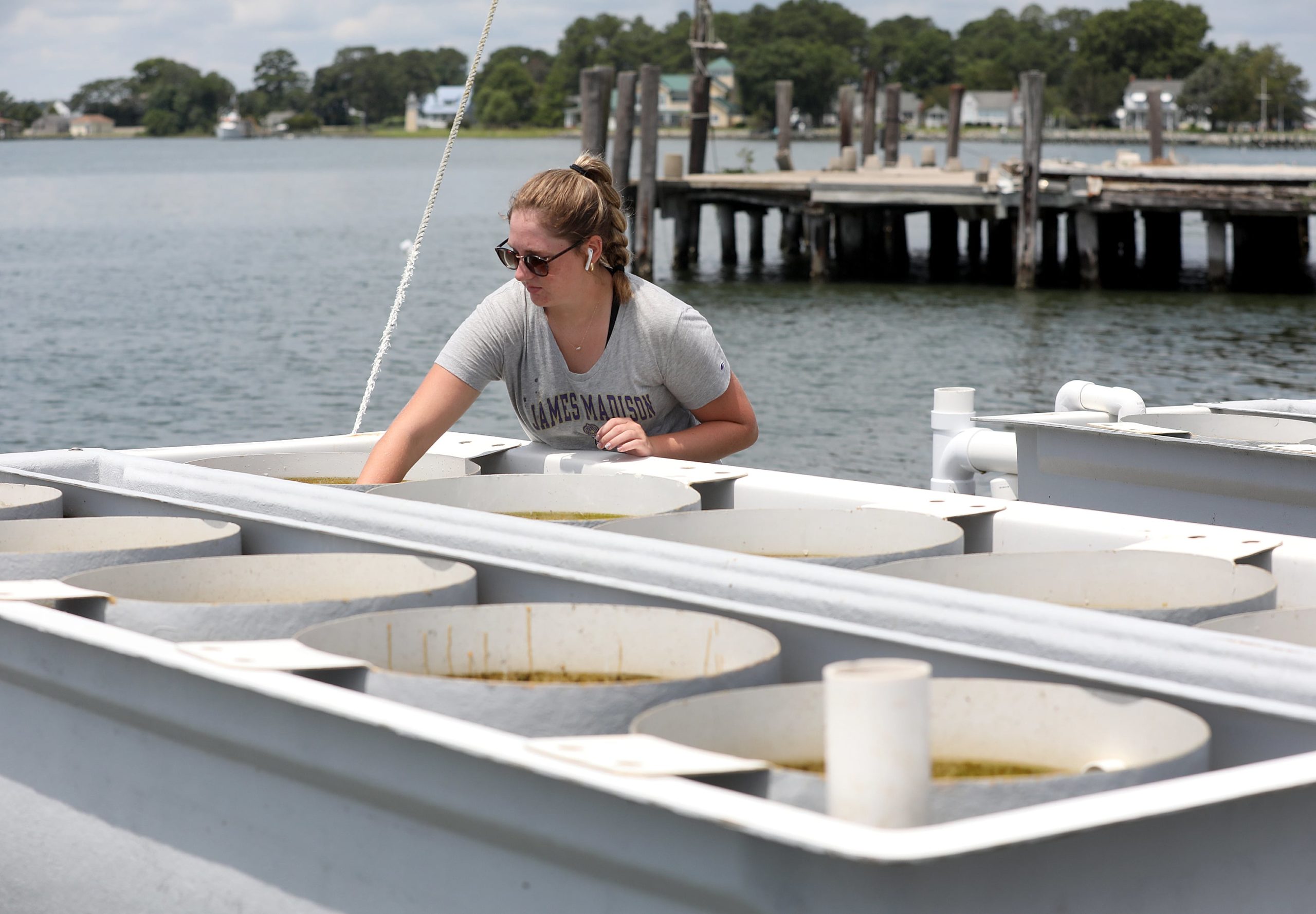

Oyster Seed Holdings grows its own algae, too — in fact, trillions of cells of algae are produced daily — to feed the broodstock, larvae and seed. That process starts with large vessels of bubbling, colored fluids of single-celled plants or microalgae.

After the oysters spawn, the eggs are collected, fertilized and put into 4,500-liter tanks to be monitored on the production floor. Those embryos turn into oyster larvae that feed off the algae for roughly two weeks.

“Every other day, we drain the larvae down, we collect them on screens, make sure they’re eating well and make sure they’re healthy,” Congrove said. “We clean the tanks, refill them with seawater and put the larvae back in the tanks. We make sure they’re fed and happy.

From there, the larvae undergo what Congrove calls “a real metamorphosis.”

They are free swimming larvae oysters for the first two weeks of their life. Afterward, they swim to the bottom and glue themselves in place to substrate.

“Once that larval shell is glued in place, they lose their ability to swim,” Congrove said. “They rotate their internal organs 180 degrees and really maximize the size of the gill.”

That gill turns them into pumps, where they can bring their own food in.

They are grown a bit larger in the hatchery before they’re ready for farmers. They’re sieved, sorted by size, and grown in the best environment possible. Once they’re 1-millimeter in size, they can be picked up at the hatchery or shipped overnight to farmers.

The seed is packed onto a screen and serves oyster farmers from Rhode Island to Florida. “We try to be a source for as many companies as we can,” Congrove said. “We started our first season producing 15 million seed. Now we produce about 115 million seed every season.”

Oyster Seed Holdings held tours over the summer to show off its operation and get people excited not just about the wonderful taste of oysters, but just how special they are for everyone who appreciates coastal living and the water as a way of life.

“We think that oysters are a key to environmental restoration in water bodies,” Congrove said. “They’re a cool food for people to get together and enjoy. The aquaculture process provides a way to get oysters back in the water in large numbers.”